From Washington through Trump

(Revised and updated 10/24/2022)

The text of Presidential thanksgiving proclamations reveals a the dramatic evolution of the idea and meaning of Thanksgiving Day. Thanksgiving proclamations began as a call to participate in a day of solemn reflection and expression of thanks to a Supreme Being. Over time, however, the Thanksgiving Proclamation has evolved to evoke a distinctively American history and celebration of certain core values. (Jump to the list of proclamations)

Washington (in 1789 and 1795) and Madison (1815) proclaimed that there be a day of reflection and public thanksgiving for peace and abundance. Prior to that time and continuing afterward, days of thanksgiving had been observed in individual colonies and states. It was especially well-established as a family “domestic occasion” in New England. (Pleck, 775).

Lincoln’s second 1863 Thanksgiving proclamation began a national holiday tradition with a standardized date—the last Thursday in November. Lincoln called for a day of “thanksgiving and praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the heavens” as well as “humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience.” Subsequent presidents followed Lincoln in specifying the "last Thursday."[1]

However, sometimes November includes five Thursdays, and in those cases Thanksgiving is always very close to Christmas. Merchants learned that most Christmas shopping was delayed until after Thanksgiving. In response to concerns that a “late” Thanksgiving would reduce consumer spending, Franklin Roosevelt, in 1939, proclaimed the observance to be on the fourth Thursday in November (November 23 vs Nov 30 for the last Thursday in 1939).

Not all states followed Roosevelt's lead, with nearly half observing the traditional “last Thursday” rather than the fourth. FDR’s controversial decision was codified by Congress in Joint Resolution signed by Roosevelt on December 26, 1941 (H. J. Res 41).

Starting about this time, the language of Thanksgiving Day Proclamations changed to emphasize American values and ideas, and to assert the event's direct link to the “first Thanksgiving” of Plymouth Colony.

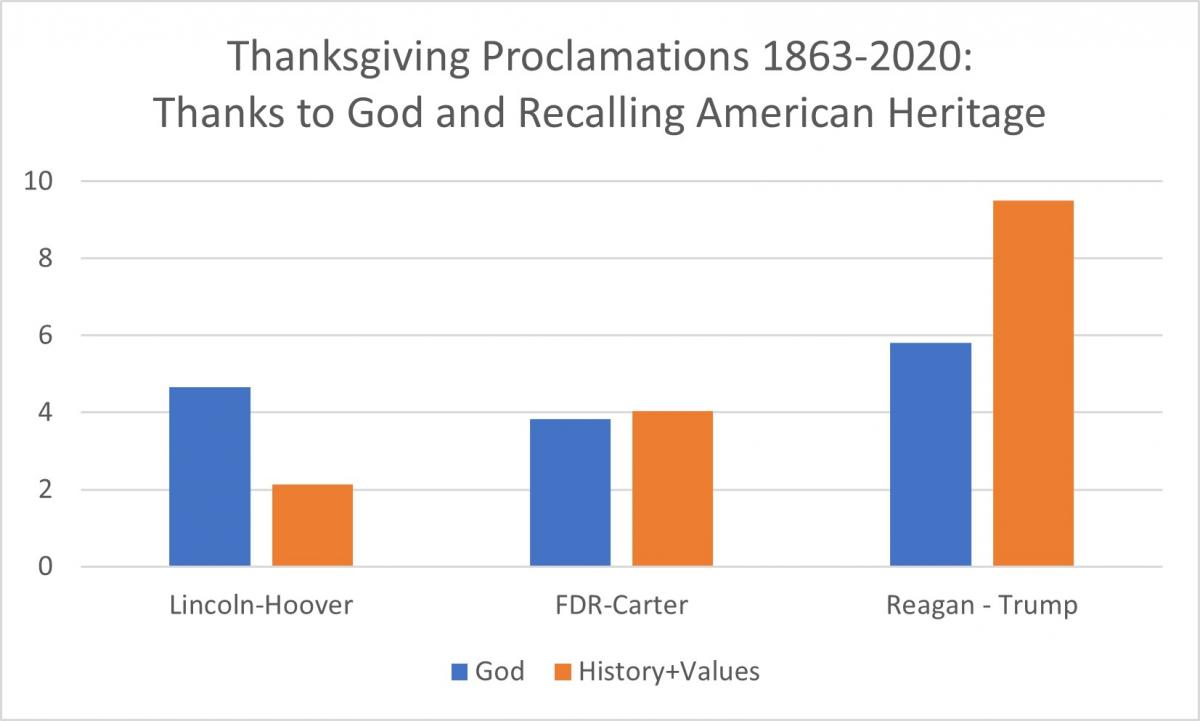

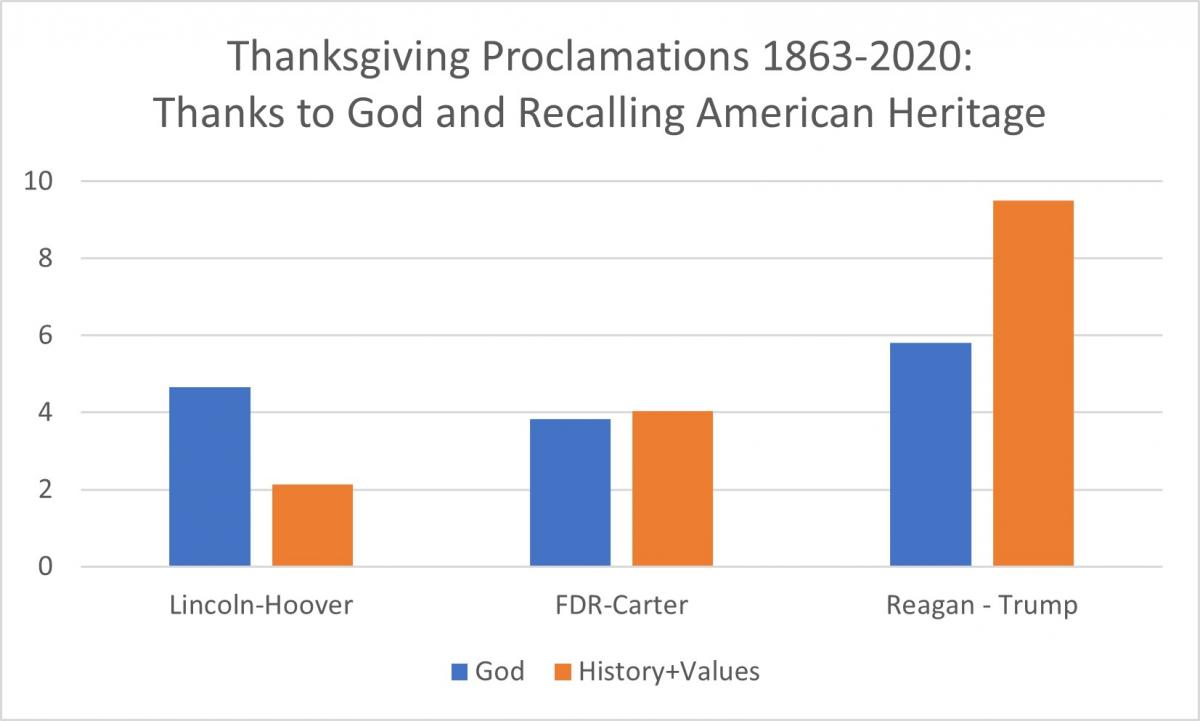

In examining this evolving language, we contrast three periods in the history of the presidency: Lincoln through Hoover (1863 -1932); FDR through Carter (1933 - 1980); and Reagan to the present (post-1980). Altogether, as of 2020, there have been 163 instances of Thanksgiving Day proclamations. Of those, 88 (or 54%) are after 1932.

A consistent feature of Thanksgiving Proclamations throughout is reference to a Supreme Being.[2] These terms are used nearly five times on average in every proclamation except three, when there are none: Nixon 1969; Ford 1975, and Obama 2016. Fifty-three percent of these "Supreme Being" references are in post-1932 proclamations—almost exactly the proportion of post-1932 Thanksgiving proclamations.

However, after 1932, Thanksgiving Proclamations more strongly emphasize the story of the “original” Thanksgiving of the Plymouth Colony and regularly instruct citizens to recall America’s unique commitment to values of liberty, freedom, human dignity, community, and democracy.[3] Rather than simply expressing gratitude for, and reflecting on, peace and prosperity, Thanksgiving Day became a celebration of a distinctive, and perhaps idealized, American history.

All, or nearly all, specific historical references (Plymouth, Pilgrims, Indians, Wampanoag, settlers) have been in proclamations from the post-1932 period. Indeed, the specific references to the Wampanoag are mostly after 2009.

The general historical trend is illustrated in this graph, contrasting the average number of references to a Supreme Being with references to American history and values (based on our search terms listed in footnotes).

Date

President